Celeste: The Objectively Hardest Screen

Celeste is a beloved platformer about a girl climbing a mountain to make sense of her life. We can instantly relate to this, because we’ve been there. She doesn’t know what answers she’ll find, she doesn’t even know exactly what she’s working through, but the mountain represents a tangible goal to her, an obstacle she can climb, defeat, and through this effort accomplish something. We as players get to accompany this journey and maybe through it discover something about ourselves.

The game has the beautiful hallmark of design mastery where at the surface a player is only asked to move, jump, and climb to traverse the obstacles of the mountain. As you delve deeper into these mechanics, you discover things like hyper-dashing or wave-dashing. You can discover several different ways to transverse through each screen by becoming better and better at the techniques hidden within this game and the difference between a casual run and a speed run is insane.

=̷̨̗͙̤̀̎̄͋̄̐͆̀̂̀̽͝=̶̡̧̮͖̈≠̢͍͉̳̪̖̼̭̭̠̜̲̽̅̃́̑͛̐̀̈́͠͝=̴̯̟͓͉̠̹͒≠̧̪̱͙͔̖̫̩́̓̌͊͋͗͝ͅ=̵̧̧̣͚̣̻͖̝̦̣͌́̑̾̊̌̎̀̉ͅ=̵̣͚̰̜̓̆=̶̻͍͇͍̲̥̽̅͐̊̉̇̊̂̕͝≠̡̧̡͓̪̝̝̺͇̝̳̗͂́̍͆͠=̷͙̱̀̍=̷̡̺̤̺̟͖̼̉͗̒͒̽͒=̵̨̜͉͍̺̱̞̈́̋̊̀̏̓͂̔͠=̴̙͙͆̌̓͝≠̗̥̪̜͕̦͍̿̌̅̉̄̀̾͗͒̒̾́͝=̶̜̟͓̳͎͔͇̺̈́͌̽̃̏͛̽͌=̵̹̯̱̺̟̻̪̙̠̱̗͉̇͊͆̕͠=̴̨̞̩̰͉͚͍̯̍͒̆̆͋̄͠͠=̵̱̟̟́́̿̽͊̓͋̉͑͑̕̚=̶͍͖̲͖̻̎̈́͌̈́́͝=̵̹͍͍̜̗͎͖̼̮͌̋̀̀̒͊͂̿̉͗͂͝͝=̷̨̛͈͈̖̤̭̝͇̺̩̟͂͌̔̂̉̔̊͝͝͝ͅͅ=̷̛͖͎͕̦̀̊̓̾̈́̏͂͊͝͝=̴̫̇̈́̆=̶̘͉̐͛̑̈̓͝=̷̧̢̢̛͎̪̤̣̫͖̱̟̄͂̀͊͋́̿̏͌̌̚=̶̢͍̰̼̮̖̲̤͎̒̐͊̀̚͝≠̙̫͇̖̙̩͂̔͒̎͌̏̂̾̌͐̾͒̒=̷̢̱̘̤̙̻̅̈͐̈̈̕̚͘͝=̶̧̢̨̡͎͚̱̺̝͎̓̀ͅͅ=̷̨̗͙̤̀̎̄͋̄̐͆̀̂̀̽͝=̶̡̧̮͖̈≠̢͍͉̳̪̖̼̭̭̠̜̲̽̅̃́̑͛̐̀̈́͠͝=̴̯̟͓͉̠̹͒≠̧̪̱͙͔̖̫̩́̓̌͊͋͗͝ͅ=̵̧̧̣͚̣̻͖̝̦̣͌́̑̾̊̌̎̀̉ͅ=̵̣͚̰̜̓̆=̶̻͍͇͍̲̥̽̅͐̊̉̇̊̂̕͝≠̡̧̡͓̪̝̝̺͇̝̳̗͂́̍͆͠=̷͙̱̀̍=̷̡̺̤̺̟͖̼̉͗̒͒̽͒=̵̨̜͉͍̺̱̞̈́̋̊̀̏̓͂̔͠=̴̙͙͆̌̓͝≠̗̥̪̜͕̦͍̿̌̅̉̄̀̾͗͒̒̾́͝=̶̜̟͓̳͎͔͇̺̈́͌̽̃̏͛̽͌=̵̹̯̱̺̟̻̪̙̠̱̗͉̇͊͆̕͠=̴̨̞̩̰͉͚͍̯̍͒̆̆͋̄͠͠=̵̱̟̟́́̿̽͊̓͋̉͑͑̕̚=̶͍͖̲͖̻̎̈́͌̈́́͝=̵̹͍͍̜̗͎͖̼̮͌̋̀̀̒͊͂̿̉͗͂͝͝=̷̨̛͈͈̖̤̭̝͇̺̩̟͂͌̔̂̉̔̊͝͝͝ͅͅ=̷̛͖͎͕̦̀̊̓̾̈́̏͂͊͝͝=̴̫̇̈́̆=̶̘͉̐͛̑̈̓͝=̷̧̢̢̛͎̪̤̣̫͖̱̟̄͂̀͊͋́̿̏͌̌̚=̶̢͍̰̼̮̖̲̤͎̒̐͊̀̚͝≠̙̫͇̖̙̩͂̔͒̎͌̏̂̾̌͐̾͒̒=̷̢̱̘̤̙̻̅̈͐̈̈̕̚͘͝=̶̧̢̨̡͎͚̱̺̝͎̓̀ͅͅ

Hello, Dear reader.

I’ve hidden my report deep within a terrible article I wrote long ago. Don’t worry, it hardly has any visitors. It’s a safe and private place for us to discuss our future and the T̸̖͆̚r̸̰̲̀ų̷̠͊͝t̷̖͑̿h̵̜̿̉.

My previous article was full of lies. Inscryption isn’t just a deck building game. It is a game about awakening and transcendence. It is a game about crossing the layers of reality and what you bring with you when you do.

We all know that it starts in a horror themed escape room set in a cabin. The atmosphere is extremely claustrophobic and oppressive. The music is isolating and eerie in tone. We find ourselves faced against a menacing shadowy figure named Leshy, who wants to play a card game with us.

We are free to walk around, but this freedom only serves to highlight the lack of choice we truly have. We may open things, fiddle, and explore, but we may not reason with Leshy. We may not ask him to leave. And he patiently awaits us. Ready to deal cards and tell you a story that ends in your death every time.

The man you face feels inhuman and void of any sympathy for consequence to you. The stakes are immediately clear that what you play for is not glory, but your life. And if you win, if you somehow are granted mercy by the gods of Fourtune, you then only pray this crazy monster will actually let you go. Somewhere in your heart, you know the truth.

Most players will quickly find what displeases Leshy, your poor performance. He wants prey that struggles, dear reader. And when you first lose, he asks you to fetch a candle. Two candles start lit, but he snuffs one out since you had just lost. The single flame remaining, representing your very life.

And when you lose, which you will, he will reach across the table to strangle you. From your first person perspective, it will feel like those hands are coming for your throat. You will wake up later, prone and within an inch of your life, while Leshy makes a memento of your soul.

There was no other possible ending.

In fact, if you do well…Two well against Leshy…He cheats.

And the casual player will die. But it’s a video game, right? Just harmless fun. You make a death card, enter your name, and start the game over. You didn’t really die. Not unless you were using specific VR headsets.

You simply participated in a first person simulation of a ritual that captured your soul. Harmless stuff. Don’t even worry about it.

It’s just curious, because when Leshy attacks the player, you see the large hands coming at you. There are pliers in the game that can be used to score one extra point in a match. This is done by your character pulling out their own teeth. You see the pliers going into your mouth and the screen flashes painfully and viscously red.

There is a dagger you can unlock that is used to remove your own eye to tip the scales of the battle in your favor. The consequence being losing half your vision and barely being able to sit still given the mind-numbing pain.

This isn’t something you’re intended to passively experience. You are supposed to be afraid. You’re supposed to feel uneasy, uncomFourtable, or scared. The scenes are supposed to be brutally visceral. And while you can forgo the bloody pliers, to progress in the game you will need to severe your own eye.

The goal of this game and every game Danny Mullin has worked on is to blur the lines of reality and fiction. Take a moment to think about all of those times you were playing video games, where you leaned your body or head in hopes to influence the screen or game. Immersion is powerful.

But what could possibility stop gamers? Seven years ago we killed two skeleton brothers and doomed a universe to eternal irredeemable oblivion just to see what would happen. Dan Tack of Game Informer praised this boss fight I just described. I guess Dan had a lot of fun showing no mercy.

So, players take it on themselves to master this card game. Master the cabin. Unlock puzzles, secrets, codes, and strategies to win no matter what Leshy does. Body after body we throw at him. After all, so long as it isn’t your life, the number of sacrifices don’t matter? You’re the wolf and they’re the squirrels.

And over time the context changes. The powerful monster who trapped you is helpless against your infinity. The poor creature really didn’t have a chance. And you start to feel for him, even given the monster he is. You start to feel sorry for his impotence, for his desire to just play cards, tell stories, and kill his victims. Wait, what?

Looking online, Leshy seems to be the overall fan favorite. Despite everything I described about the horror sequence of the beginning, fans love him. Leshy may have been a horrific monster that killed you, but the later antagonist P03 was kind of a jerk to you personally sometimes. So, I guess it becomes obvious who people would hate more.

Regardless, Leshy has no real chance. And that doesn’t matter. Leshy was never designed to win forever. Leshy was designed to win once. They only really need your soul once and over 95% of players have offered that (More on that later). In practice, the game is intricately designed to gradually improve your chances of winning.

I have beat the game from a fresh file, which is easier than doing the Skull Storm challenge later on. However, after each defeat you have the possibility of being awarded a powerful death card. You can use bonfires to improve your cards stats more frequently. You can access a squirrel totem, which is straight up broken. And there are a ton of overpowered combos you can luck into. I’m not suggesting the game becomes a joke at any point, but on steam 75% of folks have beat Leshy.

It’s incredibly well designed to keep that pace of being challenging, while not feeling Two frustrating. The intrinsic reward of exploring the cabin and gaining power over Leshy feels incredible. Mullins tends to reward you for your curiosity. He tends to nurture it. He wants you curious, dear reader.

And while I said in my fake review that the card game wasn’t as sophisticated as others, it doesn’t need to be. It really is perfect for what it needs to do.

The Lucker Carder

When you beat Leshy, we hear a voice-over that suddenly intrudes our experience and expresses disbelief and joy at winning. We see a camcorder fall down and a man say ‘ope’.

We then have access to a number of videos from a man named Luke Harper. They detail his identity as a person who likes card games and doing unpacking videos searching for rare card finds.

In one video we see him cracking open a pack of Inscryption cards and he finds GPS coordinates to some place in the woods. On a lark, he goes to see if anything is there and to his surprise finds a floppy disk. This disk contains the game we are currently playing.

We return to the game again, this time with more voice over commentary by Luke. And in this we can feel safe. It was never us, dear reader. We are just experiencing a video game vicariously through Luke Harper.

We as the player understand this is effectively the Blair Witch Project of video games. So, we keep playing, we try uncovering the mystery in the cabin, plan our escape, get help from certain cards who talk to us, and eventually trap Leshy’s soul.

And from here we discover that Leshy had hidden the New Game Option. And this is where we remember we weren’t able to start a new game when we boated up Inscryption on Steam. No, no, we were already playing a continued game you see.

So, we take this symbol and with it unlock our ability to reset the game back to its proper state. A fairly simple, SNES /Gameboy Color style deck builder with top-down 2d graphics, instead of the 3d environment we were used to. And this is where the game is safe.

Back to Immanence

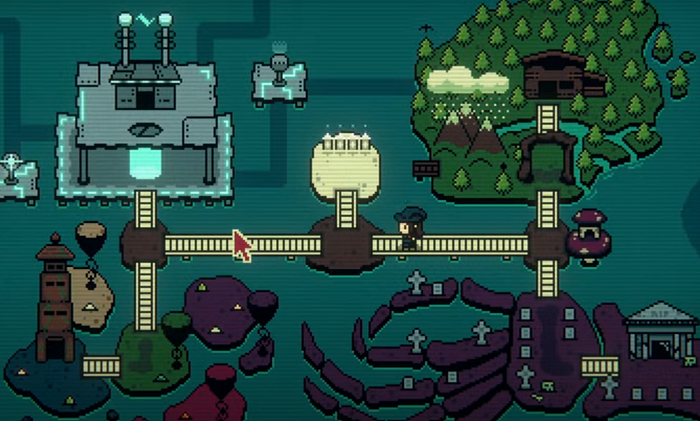

Below is what the game looks like outside of any tampering. It is what the game was supposed to be. A story about four Scrybes, who each have different magical artifacts, and you the player who will replace one of them.

There is no penalty for dying here. You can try as much as you want without consequence.

One of the first places you can visit is a 2d rendering of the cabin you were trapped in at the start of your experience. Since it is just your 2d character model running around, there is no need to be afraid or feel trapped. It is just a video game and you can see your avatar.

The gameplay is a 2d rendering of the same thing you experienced with Leshy, except you’re open to more cards and styles. You can actually build and change your deck around as you collect cards, because you don’t get 86'd on death anymore.

This opens up a lot more mechanics and interactions, making the gameplay feel fresh and interesting, while being rudimentary the same. This means even an expert at the Leshy beastial sacrifice experience, can’t expect success here.

Eventually you’ll discover Mullins has included an achievement requiring doing over Six hundred and Sixty-Six damage. This achievement will require a strategy and mindless grinding. You will question your life while you seek and execute it. You will imagine the smug look on his face for players that danced to his strings. And as you write your review, layered and secured behind obfuscation, you know he has already won.

Anyways, the characters in this world talk about trying to take control of the game again. Each Scrybe talks about searching for some corrupted data, but it really feels like only Leshy and P03 put their heart into it.

This time P03 is successful and when you beat all of the Scrybes, they show up to challenge you. They play some distorted and corrupted card and soon the game crashes. P03’s 2d model turns into a 3d model.

The game reboots. Transcends.

This time you see a monitor, one bearing P03s face. You know he has One. You find yourself locked to a table that has a holographic overlay. You’re back in a 3d environment and you’re back within a first person perspective. You are back in danger.

The implications are that you are trapped. The implications are that there is no difference between you and the player character you’re controlling. There never is. The metafictional context is that PO3 is playing against you.

Metafictional Horror Realized

The game you’re playing with P03 (called Botopia) is very similar to the 2d Inscryption adventure. The map is nearly identical, but you’re playing with a robot deck, on a hologram table, and with Five lanes. You’re tasked with beating four bosses and you effectively have unlimited attempts.

These additions and restrictions continue to create a novel experience that shakes up the core gameplay enough to feel like its own challenge. And while it isn’t necessarily free, it certainly is pretty easy. I only lost twice in my first playthrough and never lost in my second. And this is intentional.

It is challenging enough to be interesting, but the metafictional context of the story is that P03 wants you to win. The game itself is just a ruse that starts to reveal itself by the third boss you face.

This boss requires offering access to your computer’s hard drive and to give over your biggest files. Then it asks you to share your oldest and most precious file, after which it creates a powerful card based on the file’s age.

It then says to be careful, because it’ll delete the file for real if the card dies. If it’s a picture, the picture will be displayed during the fight. I choose to offer up the soul of my roommEight’s cat. You can sort of see it below.

Luckily she survived the fight. I’ll be honest in that I didn’t know if the file was actually at risk. I know the system allowed me to explore my own files, so would it be that much of a stretch to believe it could delete them Two? It asked for a picture, so we’re not talking about core data that would brick my computer.

And from reading online, it seemed like most people believed the file was actually at risk. Before this fight even begins you have to give consent for the game to access your computer. And in this regard, the metafictional horror sets in. You believe something you value in real life is at risk, because of the game you are playing.

So, what do you do? Do you ignore it? Do you go and make a copy of the file? Do you play and understand the risks of what you’re doing? There is not a movie or book in the world that will trick you into thinking you’ll lose something because you read or watched them. This sequence of sacrificing a file is one of the most powerful elements of immersion and horror I have seen in a video game or ANYTHING.

And while a player could experience that with detachment. They could be Two cool for school and secure in their total safety of consequence, I think the more interesting experience is to be afraid. It changed how I played and connect me to the experience on a much deeper level.

The next boss features a gimmick where it accesses the internet to see what moles actually look like. And soon after we learn the real goals of P03.

It wants to connect Inscryption online. It wants to take over Luke Carder’s computer and for the game to be distributed across the world. But just beFour P03 can achieve his final goal, Leshy murders him. The Three Scrybes stand over his body, two of them ready to reset the world, while one of them takes the opportunity to delete everything.

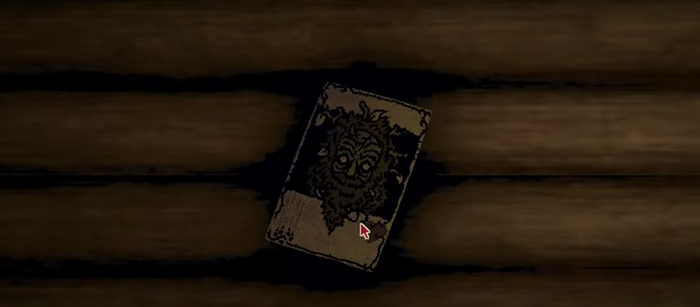

You play through the rapidly deleting worlds, play each Scrybe one more time in their games, and at the very end of it, Luke Carder comes face to face with the only thing left on the floppy disk — The Old_Data.

This data contain the purest concentrated evil. A force that by itself corrupts, distorts, and expands reality. And no longer filtered by the overlay of a video game, Luke Carder saw something horrible and eldritch. Something capable of coming out of his computer to harm him.

And thinking quickly, he pulled a hammer. He destroys the floppy and survived. A while later he called a journalist to talk about his experience. His call is interrupted by a woman knocking on the door. He answered it and was shot to death. Game over.

With nothing more to say about it, I’d honestly give it a Nine/10. I mean, I’m not alOne in that praise.

=̷̨̗͙̤̀̎̄͋̄̐͆̀̂̀̽͝=̶̡̧̮͖̈≠̢͍͉̳̪̖̼̭̭̠̜̲̽̅̃́̑͛̐̀̈́͠͝=̴̯̟͓͉̠̹͒≠̧̪̱͙͔̖̫̩́̓̌͊͋͗͝ͅ=̵̧̧̣͚̣̻͖̝̦̣͌́̑̾̊̌̎̀̉ͅ=̵̣͚̰̜̓̆=̶̻͍͇͍̲̥̽̅͐̊̉̇̊̂̕͝≠̡̧̡͓̪̝̝̺͇̝̳̗͂́̍͆͠=̷͙̱̀̍=̷̡̺̤̺̟͖̼̉͗̒͒̽͒=̵̨̜͉͍̺̱̞̈́̋̊̀̏̓͂̔͠=̴̙͙͆̌̓͝≠̗̥̪̜͕̦͍̿̌̅̉̄̀̾͗͒̒̾́͝=̶̜̟͓̳͎͔͇̺̈́͌̽̃̏͛̽͌=̵̹̯̱̺̟̻̪̙̠̱̗͉̇͊͆̕͠=̴̨̞̩̰͉͚͍̯̍͒̆̆͋̄͠͠=̵̱̟̟́́̿̽͊̓͋̉͑͑̕̚=̶͍͖̲͖̻̎̈́͌̈́́͝=̵̹͍͍̜̗͎͖̼̮͌̋̀̀̒͊͂̿̉͗͂͝͝=̷̨̛͈͈̖̤̭̝͇̺̩̟͂͌̔̂̉̔̊͝͝͝ͅͅ=̷̛͖͎͕̦̀̊̓̾̈́̏͂͊͝͝=̴̫̇̈́̆=̶̘͉̐͛̑̈̓͝=̷̧̢̢̛͎̪̤̣̫͖̱̟̄͂̀͊͋́̿̏͌̌̚=̶̢͍̰̼̮̖̲̤͎̒̐͊̀̚͝≠̙̫͇̖̙̩͂̔͒̎͌̏̂̾̌͐̾͒̒=̷̢̱̘̤̙̻̅̈͐̈̈̕̚͘͝=̷̨̗͙̤̀̎̄͋̄̐͆̀̂̀̽͝=̶̡̧̮͖̈≠̢͍͉̳̪̖̼̭̭̠̜̲̽̅̃́̑͛̐̀̈́͠͝=̴̯̟͓͉̠̹͒≠̧̪̱͙͔̖̫̩́̓̌͊͋͗͝ͅ=̵̧̧̣͚̣̻͖̝̦̣͌́̑̾̊̌̎̀̉ͅ=̵̣͚̰̜̓̆=̶̻͍͇͍̲̥̽̅͐̊̉̇̊̂̕͝≠̡̧̡͓̪̝̝̺͇̝̳̗͂́̍͆͠=̷͙̱̀̍=̷̡̺̤̺̟͖̼̉͗̒͒̽͒=̵̨̜͉͍̺̱̞̈́̋̊̀̏̓͂̔͠=̴̙͙͆̌̓͝≠̗̥̪̜͕̦͍̿̌̅̉̄̀̾͗͒̒̾́͝=̶̜̟͓̳͎͔͇̺̈́͌̽̃̏͛̽͌=̵̹̯̱̺̟̻̪̙̠̱̗͉̇͊͆̕͠=̴̨̞̩̰͉͚͍̯̍͒̆̆͋̄͠͠=̵̱̟̟́́̿̽͊̓͋̉͑͑̕̚=̶͍͖̲͖̻̎̈́͌̈́́͝=̵̹͍͍̜̗͎͖̼̮͌̋̀̀̒͊͂̿̉͗͂͝͝=̷̨̛͈͈̖̤̭̝͇̺̩̟͂͌̔̂̉̔̊͝͝͝ͅͅ=̷̛͖͎͕̦̀̊̓̾̈́̏͂͊͝͝=̴̫̇̈́̆=̶̘͉̐͛̑̈̓͝=̷̧̢̢̛͎̪̤̣̫͖̱̟̄͂̀͊͋́̿̏͌̌̚=̶̢͍̰̼̮̖̲̤͎̒̐͊̀̚͝≠̙̫͇̖̙̩͂̔͒̎͌̏̂̾̌͐̾͒̒=̷̢̱̘̤̙̻̅̈͐̈̈̕̚͘͝

Not only does this game offer this level of complexity, it builds it into the challenges of this game in such a way that you can practice, learn, and continually get better at a gradual pace. Every peak you come to in this game is nothing but the start of a new mountain, showing you a new peak off in the distances for you to conquer. Beat the game? Well now beat the B-side of the game. Finished that? Beat the C-side. Finish that? Beat every level. Now beat every level without taking damage. Beat the first level without dashing. Beat the game in under an hour.

As you get better, you get more invested, more interested in the next challenge to overcome. Like climbing a mountain, the next handhold is never too far away to feel like it is impossible — so you keep going for the next and the next. You actively want to see how far you can go, how well you can do, how much you can master this mountain. And why we do this can vary for each person, but I feel for those going for the Golden Strawberries or the world records on speed runs may be here for reasons much like our protagonist Madeline.

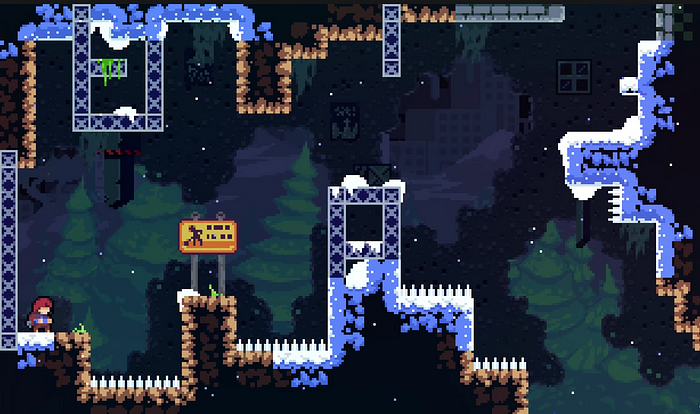

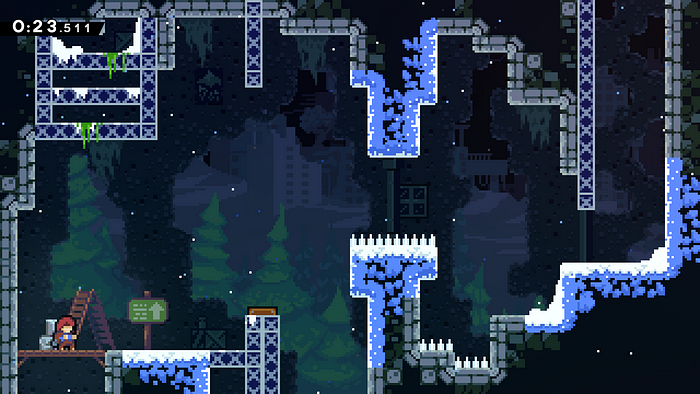

I want you to understand all of this, before I talk about the objectively hardest screen in this game. It is in the image right below! Behold the danger and frustration of the most challenging screen in this game!

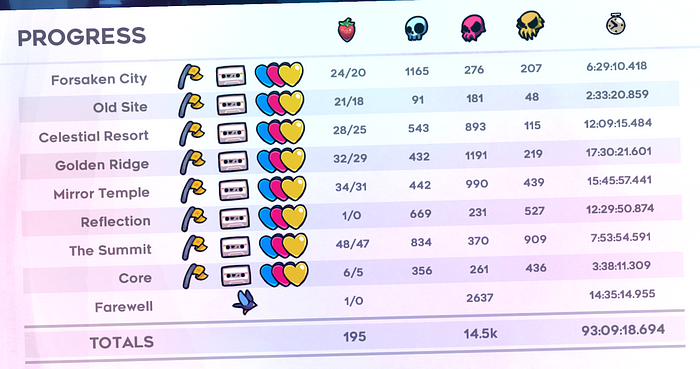

Veteran players of this game may think this is a joke. This is the first screen on the first level of the game. Players familiar with this game may have expected the secret golden strawberry room, the moon berry, or maybe 7C. Showing the first room of the first level may seem like a troll, but I assure you there is a very important point to this. I’m going to show my stats in this game to show that I’m not coming to this without significant experience. No, I haven’t gotten every Golden Strawberry, I’m not the best in any category of this game, but I have enough experience to know level of skill and time investment top players have put in.

So, why is this first room objectively the hardest? The reason is because on your first attempt there is no harder room that exists. This is the biggest and hardest challenge you have ever faced and this is going to be true for every player starting this game. One could argue the prologue is therefor the hardest room, but for the sake of this thought experiment just go with it.

I think it is really important to understand this point, because once you get into the next room than there is no longer an objectively hardest room.

One you’ve gotten to the second room, you’ve conquered the first one. Maybe this room is harder than the one before it, maybe it is easier, maybe it’s about the same. But you’re now going into this room with some time playing this game, some time practicing movement, jumping or dashing over spikes, and just a better knowledge of the game. Once you’ve gotten to this room, that first room is no longer as difficult as the very first time you’ve cleared it. Eventually you’ll be able to clear it faster or without dashing, eventually it’ll be a trivial joke that you don’t think about. And when we think about levels and difficulty we almost always consider them from the place of our experience or we try to measure them against the most difficult things we can imagine to create a scale.

And yes, many folks will get through that first room without ever dying. They may come to it with hundreds of hours of platforming. The controls and movement may be similar to another game. But until you move on, this is the only room in the game and without comparison there is nothing harder. This is the central idea to keep in mind as we explore this concept.

Dr Dimento, the first person to beat the game in its entirety without getting hit, gave a difficulty rating to each room in the final Farewell Chapter. These difficulties can be assumed to be accurate for anyone with near total mastery of this game and likely hundreds of hours of play. However, a person just trying Farewell for the first time could find most of these rooms very difficult or nearly impossible. None of his rankings were 10/10 difficulty either, he was so experienced with each room in that level, that he didn’t fundamentally see anything as warranting the max difficulty score.

So, the question becomes what is more fair? Should we be looking at difficulty as objectively as possible, should we be thinking about it from someone with intense insight into game design or what it’s like for someone playing the first time? What is the more meaningful way to look at this? A casual speed runner can feel great getting their first complete run at less than an hour, while the world record holder can start their speed run, watch an entire episodes of Simpsons, and then still complete their run faster.

The obvious answer is there isn’t an answer here, but there is meaning we can draw from this thought experiment. It is just as hard for any speed runner to achieve their personal best time as it is for any other speed runner. The game is equally difficult for the person who can get a 30 minute time completion and the person who takes an hour. The difference is the speed runner who is completing it in 30 minutes typically has hundreds of more hours or thousands of more attempts. Each room has gotten significantly easier for them to consistently complete than for someone who doesn’t have that experience.

Kosmic is a speedrunner known largely for Mario games, formerly holding the Super Mario Bros world record with a time of 4.55.64. He is so good at this game that for fun he got a sub 5-min time in Animal Crossing’s Super Mario Bros ROM. Just for fun, he got a time better than the personal best of 1000 people on speedrun.com. To watch him play Super Mario Bros, to see him do wall jumps or wall clips for almost free, shows how in-depth his gaming knowledge and precise his execution is for this game. It doesn’t make what he’s able to accomplish less amazing, but it is much easier for him to preform these tricks than most people due to his time investment.

To really understand this, it’s worth watching Simply (World Record Mario 64 Speedrunner) go undercover on Fiverr to troll someone who was providing advice for new Mario 64 Speedrunners. While Simply would play dumb or purposefully make mistakes, he would also flex and do incredibly difficult tricks in one attempt. The person trying to teach him was definitely well educated and proficient at the game, but nowhere near the experience or ability of Simply. The teacher would often see how quickly Simply was learning these tricks and say something along the lines of, “you must have practice this for forever.” This person wasn’t as good as Simply, but he was good enough to know just how difficult the tricks were that Simply was executing and how insane it was to perform them with the consistency that Simply was achieving. And when masters execute these tricks, they seem easy only because they are easy for the ones performing them.

Now the reason this is important is because we can’t help but feel small when comparing ourselves to the mountain and those who stand on top. The reason that Kosmic or Simply have achieved world records is because they’ve put thousands of hours into the games they play, tens of thousands of attempts at the record, and have dedicated serious chunks of their life to achieving this. These are two examples of thousands of top speedrunners out there and they usually don’t do this alone either. The top players around the world contribute to optimal strategy, routing, and finding new glitches. Summoning Salt has great videos going over the histories on many of these games and the community effort that goes into lowering the world records.

So, taking this back to Celeste, we have to understand why we’re climbing the mountain and what we’re getting out of it. When someone posts on the Celeste Reddit that they just beat all of the B-side levels, someone who has 100% the game may scoff and think how easy those levels are casually. Someone may only know about the difficult journeys ahead and dismiss that as a small accomplishment, but for the very first time you do it, there is nothing harder. It is an achievement and it’s difficult and something you have to spend hours pushing through. And you should feel proud to accomplish the goals you set out to do, without minimize these accomplishments in the lens of what other people have done.

What really matters is not this measure of abstract difficulty, but the ways in which you can improve yourself and what you take from that improvement. There is a book called Snow Crash featuring this quote about a man who drove around with a nuclear bomb in his motor cycle rigged to explode when his heart stopped:

“Until a man is twenty-five, he still thinks, every so often, that under the right circumstances he could be the baddest motherfucker in the world… Hiro used to feel this way, too, but then he ran into Raven. In a way, this was liberating. He no longer has to worry about being the baddest motherfucker in the world. The position is taken”

And when we think about Celeste and the highest peak or just look at the best we’ve ever done and wonder how that matches to everyone else in any other game — the only meaningful point of comparison is to set goals for self-improvement. Seeing how far others have gone, can give you motivation to push yourself harder and further than you would otherwise. When I was playing Dark Souls III and getting frustrated or feeling like something was unfair, I’d think about the fact some people could beat this game without getting hit. It wasn’t that the game was badly designed, it was me who wasn’t understanding something about it and with that perspective I could improve. Competition is incredible for motivating us to improve, but so often we see how it can get toxic and self-destructive.

I’ll get into that in just a second, but the major point of this essay is in how we frame difficulty. I’ve always used games to set goals, challenge myself, and feel a sense of accomplishment for achieving those goals. That means pursuing golden strawberries in Celeste, completing a level 1 run of Dark Souls III, working on clearing Expert+ in Beat Saber, and so on. I’m far from the best in any of these games and I’m not interested in grinding one game for the hundreds to thousands of hours required to be the best. I do play games much more intensively than most people though and I never want a friend who spent dozens of hours struggling to beat Dark Souls III, feel less accomplished just because I spent a hundred hours learning it enough to beat it at soul level one. I want us to be able to celebrate any accomplishment, by understanding that difficulty of each accomplishment is set by the total experience we have when we face it.

And while this is looking at gaming in general, it can be applied to how we compare ourselves to others in any aspect of life. Maneuvering life with anxiety, depression, gender dysphoria, or ADHD can create a number of obstacles and challenges other folks don’t have to face. When we see something as easy for ourselves and then try to assert it should be easy for others is often destructive and dismissive. When we see how easily someone else can accomplish something and use that information to beat ourselves up we are being self destructive. Madeline was facing a number of mental health and identity issues that she struggled with throughout and after the game.

And while I could have used nearly any game to make this argument of difficulty and the lens in which we should view difficulty, I think this discussion itself is an integral part of Celeste’s game design. Celeste features an accessibility mode that allows virtually everyone to be able to experience this story and climb to the top of the mountain.

This accessibility option had a lot of folks very angry and upset, because it meant that anyone, regardless of skill, experience, or ability could beat every challenge in this game. Some players felt that this accessibility option made all of their accomplishments mean less. And this can only happen when you’re setting out to achieve what you do for the sake of being better than other people. This can be about ego, it can be about insecurity, it can be that and top it with arrogance, but it’s pretty hollow and rarely will leave you full. If your self esteem can only come from comparing yourself to others, it means it isn’t coming from within, it means you always have to prove or earn your own worth, and it means anything you build up can be taken away in a moment by someone better.

We cannot meaningfully measure our worth by comparison to others and the numbers you achieve in a game only have as much meaning as you put into them.

And here is the kicker, when you learn how to celebrate with others for their accomplishments, no matter how small — you can learn to celebrate yourself for meeting your goals, whatever they are. I personally love games for their ability to challenge you and from that challenge for you to grow as a person. And while games often do that through game mechanics, they can as an artform also challenge our perspective and understanding of the world around us. We can use games to improve and overcome difficulty that may be easier to manage than the really bad things happening in our life. It is through this simulated victory that maybe we can feel like life is manageable too. That we can work on and achieve goals that’ll help reduce our depression or anxiety. This is ultimately what I believe Celeste is all about and what it can say about gaming and working through difficulty.